|

|

Det dynamisk skiftende indhold på denne side er sammensat af bearbejdet materiale, der fortrinsvis er inspireret af fakta fra ovenstående links. Disse links er i sig selv og i høj grad spændende og anbefalelsesværdig læsning.

Jeg påberåber mig således ingen former for ophavsret over nærværende materiale.

Jeg takker hermed for inspiration. :-)

M. Due 2025

|

|

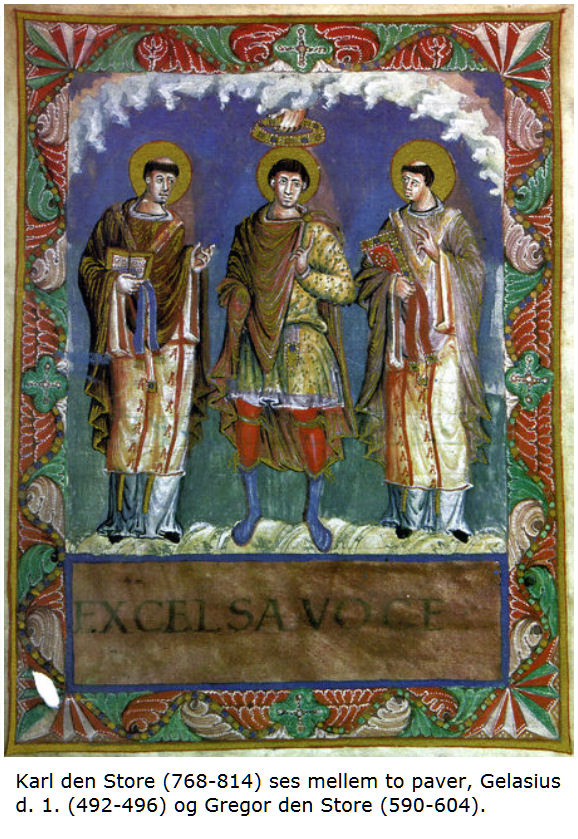

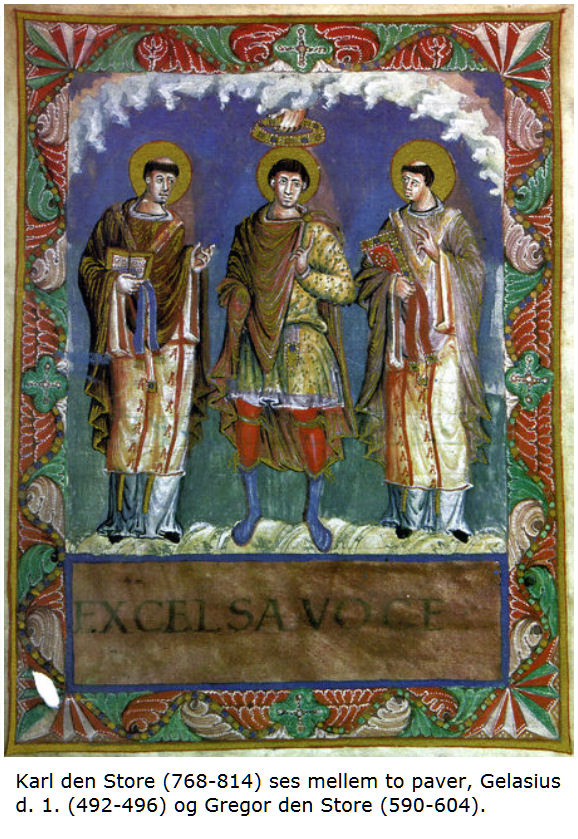

Gelasius I - 492-496 :

Gelasius I (San Gelasio I)

Pope Gelasius I (died 19 November 496) was the head of the Catholic Church from 1 March 492 to his death in 496. He was probably the third and last Bishop of Rome of North African origin in the Catholic Church. Gelasius was a prolific writer whose style placed him on the cusp between Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. Gelasius had been closely employed by his predecessor Felix III, especially in drafting papal documents. His ministry was characterized by a call for strict orthodoxy, a more assertive push for papal authority, and increasing tension between the churches in the West and the East.

Place of birth

There is some dispute regarding where Gelasius was born: according to the Liber Pontificalis he was born in Africa (natione Afer), while in a letter addressed to the Roman Emperor Anastasius he called himself "born a Roman" (Romanus natus). That said, the latter assertion probably just means that he was born in Roman Africa before it was overrun by the Vandals.

Acacian schism

Gelasius' election on 1 March 492 was a gesture for continuity: Gelasius inherited Felix's struggles with Eastern Roman Emperor Anastasius and the patriarch of Constantinople and exacerbated them by insisting on the removal of the name of the late Acacius, patriarch of Constantinople, from the diptychs, in spite of every ecumenical gesture by the current, otherwise quite orthodox patriarch Euphemius (q.v. for details of the Acacian schism).

The split with the emperor and the patriarch of Constantinople was inevitable, from the western point of view, because they had embraced a view of a single, Divine ("Monophysite") nature of Christ, which was a Christian heresy. Gelasius' book De duabus in Christo naturis ("On the dual nature of Christ") delineated the Western view. Thus Gelasius, for all the conservative Latinity of his writing style, stood on the cusp of Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages.

During the Acacian schism, Gelasius affirmed the primacy of Rome over the entire Church, East and West, and he presented this doctrine in terms that set the model for subsequent popes asserting the claims of papal supremacy, due to the succession of the Roman Popes from the Apostle Peter.

In 494, Gelasius wrote a very influential letter, known as Duo sunt, to Anastasius on the topic of Church-State relations, whose political impact was felt for almost a millennium.

Suppression of pagan rites and heretics

Closer to home, Gelasius finally suppressed the ancient Roman festival of the Lupercalia after a long contest. Gelasius' letter to Andromachus, the senator, covers the main lines of the controversy and incidentally offers some details of this festival combining fertility and purification that might have been lost otherwise. Significantly, this festival of purification, which had given its name— dies februatus, from februare, "to purify"— to the month of February, was replaced with a Christian festival celebrating the purification of the Virgin Mary instead: Candlemas, observed forty days after Christmas, on 2 February.

After a brief but dynamic ministry, he died on 19 November 496. His feast day is kept on 21 November, the anniversary of his interment, not his death.

Writings

Gelasius was the most prolific writer of the early Roman bishops. A great mass of correspondence of Gelasius has survived: forty-two letters according to the Catholic Encyclopedia, thirty-seven according to Father Bagan and fragments of forty-nine others, carefully archived in the Vatican, expounding to Eastern bishops the primacy of the see of Rome. There are extant besides six treatises that carry the name of Gelasius. According to Cassiodorus, the reputation of Gelasius attracted to his name other works not by him.

Decretum Gelasianum

The most famous of pseudo-Gelasian works is the list de libris recipiendis et non recipiendis ("books to be received and not to be received"), the so-called Decretum Gelasianum, which is believed to be connected to the pressures for orthodoxy during his pontificate and intended to be read as a decretal by Gelasius on the canonical and apocryphal books, which internal evidence reveals to be of later date. Thus the fixing of the canon of scripture has traditionally been attributed to Gelasius.

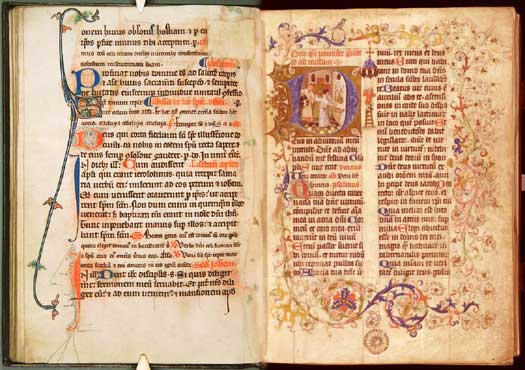

Gelasian Sacramentary

In the Catholic tradition, the so-called Gelasian Sacramentary, actually the Liber sacramentorum Romanae ecclesiae ("Book of Sacraments of the Church of Rome") is a book of liturgy that was actually composed in Merovingian times. An old tradition linked the book to Pope Gelasius, apparently based on Walafrid Strabo's ascription to him of what is evidently this book. Most of its liturgy reflects the mix of Roman and Gallican practice inherited from the Merovingian church.

Katolske begreber:

|

Ordforklaring :

Liber Pontificalis

Liber Pontificalis:[ - ]

Liber Pontificalis: eller Pavernes Bog er en af de væsentlige kilder vedrørende den tidlige middelalders historie, men den er også genstand for stor skepsis i den henseende.

På det umiddelbare plan er bogen en samling kortfattede biografiske registreringer af de første paver op til slutningen af det 10. århundrede nævnt i kronologisk rækkefølge. Hver af registreringerne består af pavens regeringstid i antal år (og herudfra kan årstallene udledes), deres fødselssted og forældre, de samtidige kejsere, indsats med hensyn til byggeri (specielt vedrørende romerske kirker), udnævnelser, vigtigste erklæringer, begravelsessted og tiden indtil næste pave var valgt og indviet. Imidlertid vanskeliggør måden, den blev til på, at man kan fæste ordentlig lid til bogen som historisk dokumentation.

Liber Pontificalis er skrevet af underordnede embedsmænd ved paveretten, og der er fundet eksempler på forvanskninger, udeladelser og forfalskninger. Registreringerne for de

første tre århundreder

er derfor nok først og fremmest interessante for historikere som eksempler på, hvad man i det 5. århundrede vidste om den tidligste katolske kirke. Fra det 4. århundrede og frem er skribenterne på mere sikker grund, selv om der stadig kan findes fejl og mangler. Granskning af teksten lader formode, at der fandtes to tidlige versioner fra før belejringen af Rom i 546, men herefter er der tale om et enkelt eksemplar. Fra begyndelsen af det 7. århundrede (omkring tiden for Pave Honorius 1.'s indsættelse) og frem indtil indsættelsen af Pave Adrian 2. er registreringerne skrevet i samtiden kort efter hver paves død og dermed rimeligt præcise, når man ser bort fra de enkelte skribenters holdninger.

Fortsættelser af Liber Pontificalis blev senere lavet og fører beretningerne om paverne videre fra omkring 1100 til midten af det 15. århundrede, men kvaliteten heraf er meget varierende.

De mange skribenters arbejde over lang tid komplicerede arbejdet med at lave udgaver af værket til videnskabelige formål. Mod slutningen af det 19. århundrede gjorde Louis Duchesne og Thodor Mommsen begge forsøget, men Mommsens udgave er dog ikke komplet. I det 20. århundrede er der udkommet oversatte og kommenterede udgaver, hvor vægten af kommentarerne har gået på den historiske troværdighed af beskrivelserne.

[ - ]

0639

|